What pension system models are there around the world?

Distribution, capitalization, notional accounts… The Spanish pension system is just one of many around the world. There are other pension models that do not depend 100% on the State and that combine a state pension with a private one.

One only has to take a look at the “Pensions at a Glance” report prepared by the OECD to see how different countries finance retirement and even how the mechanisms in the state and compulsory contribution systems are adjusted. Some countries even combine contributions to the state system with compulsory inputs to private savings.

Types of pension systems

When talking about state pension systems, they are most commonly differentiated according to the way in which they finance pensions. And there are various ways to structure the model. Here are the most common:

Pay-as-you-go system:

This is the pension system used in Spain and in most southern European countries.

This system uses the contributions of active workers and distributes these among pensioners. In other words, currently active workers pay for the pensions of retirees; this makes it a system of intergenerational solidarity. Each generation supports the previous one by paying their pensions with the money they contribute to the Social Security and in the hopes that the next one will do the same.

This model raises sustainability issues, as it depends entirely on there being a sufficient mass of workers to pay the state retirement pensions and, with an aging population, this can be a problem. For this reason, many of the countries that use a pay-as-you-go system are looking for ways to encourage private savings.

Capitalization system:

In contrast to the pay-as-you-go system are the capitalization systems. This model is based on each worker making contributions to the system and then receiving what is generated by those contributions.

In other words, it is similar to the way a pension plan or an investment fund works, where you invest capital and after some time you get that money back plus any profits or returns it may have generated.

These systems, more common in Anglo-Saxon countries, eliminate the intergenerational solidarity component. Each worker pays their contributions and the pension they receive depends on these.

The two problems with this system are: the impact of inflation (the interest that must be earned for the system to work and provide an amount that overcomes the effect of inflation); and the inequalities that can be created in line with the work history of each worker.

For this very reason, this type of system usually has a public and a private component.

Notional account system

A variant of the traditional pay-as-you-go system. Defined contribution systems, better known as notional account systems, rely on the worker’s inputs throughout their career.

The retirement pension is calculated on the basis of what the worker has contributed to an individual account that aggregates their contributions. In this way, the pension is effectively a kind of deferred salary. This is the Nordic model that is now being proposed as an alternative to the traditional pay-as-you-go system.

The notional accounts directly link the contributions to the system to the benefits that will be received, which in theory is fairer, but may not be sufficient for everyone. The main problem with this system is that it does not establish a minimum amount of income and part of the population may reach retirement without this guarantee.

The way to overcome this problem is with a basic benefit system covered by the State.

Self-enrolled capitalization system

This is the system used in the United Kingdom. What changes with respect to the traditional or basic capitalization system is that it obliges companies to include the workers in the system. Subsequently, it is the worker who must withdraw from the system if they do not want to dedicate part of their salary to these contributions.

With this small change, the system ensures that workers build up their retirement savings. From these minimum payments, either the worker themselves, the company or the State can add additional contributions.

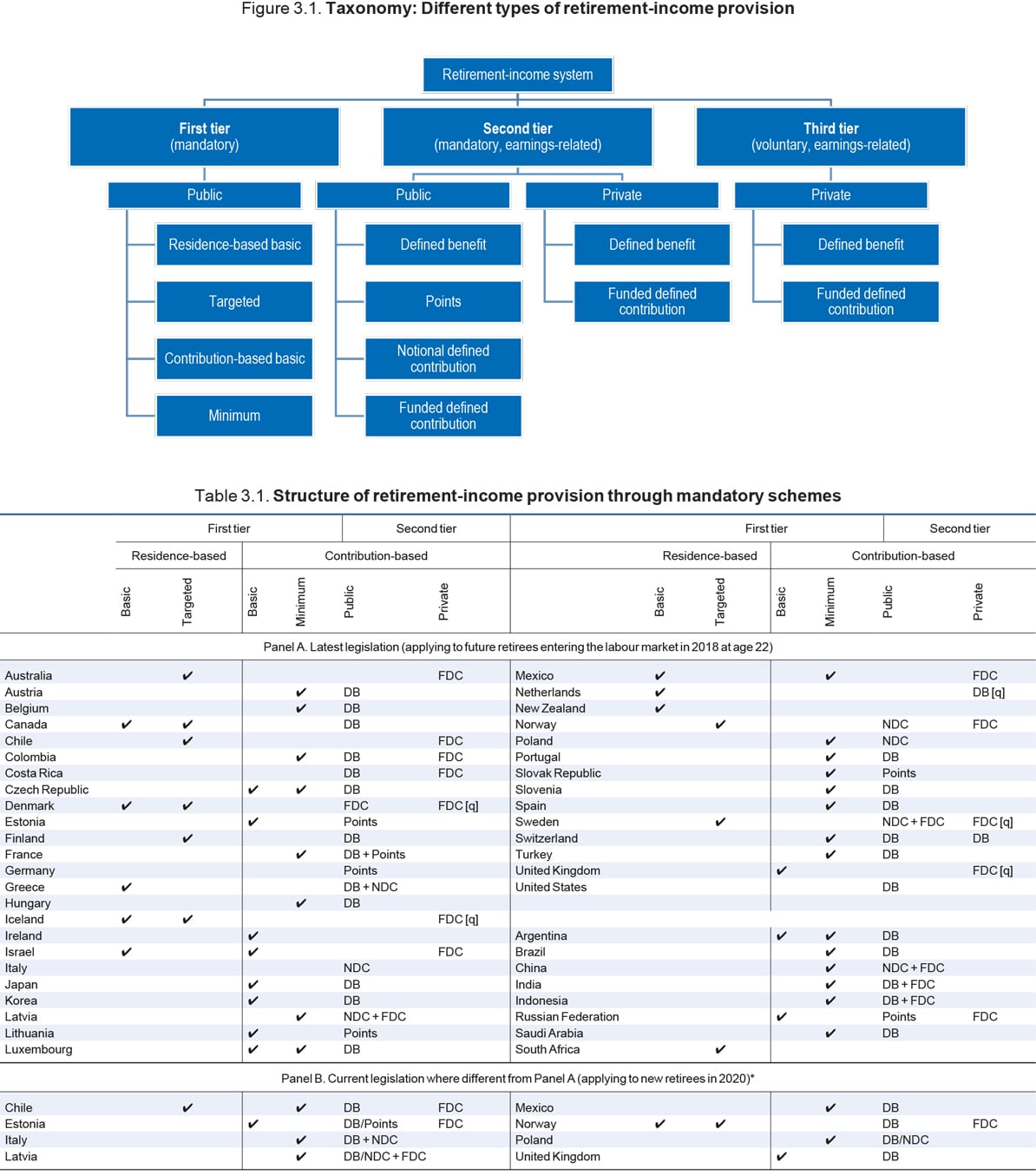

Starting from these basic systems, different combinations can be established where only the State makes inputs and the system depends on state pensions, mixed systems with mandatory contributions from the public or private sector, and voluntary systems.

This is the chart drawn up by the OECD:

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance

Examples of different pension systems around the world

There is nothing like taking a look at some of the most well-known pension models to understand the dichotomy between state and private funding, and how countries ensure the pensions of their retirees:

Pensions in Sweden

The Swedish system guides the contributions of its workers towards investment. The difference with other systems is that citizens can choose where they invest their money. Of course, this investment is mandatory.

Specifically, the State offers a number of private alternatives and one public one, which is that of the Swedish sovereign wealth fund. Then the worker chooses which one they find the most convincing (if they do not choose one, the money is invested in the sovereign fund). This competition means that the Swedish sovereign wealth fund needs to offer good results to be chosen.

The money invested by the workers is integrated into a system of individual notional accounts that are virtual.

Added to this system are company pension funds, which are more common than in Spain, and the individual savings of each worker.

In addition, Sweden has a guaranteed minimum pension for anyone who has not contributed enough and a housing supplement and maintenance allowance for the elderly.

Pensions in Norway

Norway has one of the most well-known and acclaimed pension funds within the financial community.

Norwegian workers contribute a part of their salary to this fund and their retirement then depends on how much they have paid in, the years worked, the age at which they decide to retire and the average life expectancy in the country.

The difference between the Norwegian fund and the Spanish one is how it has invested the money, helping the country’s companies on the one hand, but diversifying the assets on the other.

Norway also allows you to collect your pension and work at the same time, allowing retirees to contribute to the system.

Pensions in the Netherlands

The Dutch pension system is based on three main components and is a mixed system with a blend of state and private pensions.

The first component of the system is the state pension, which operates on a defined-benefit pay-as-you-go model. The state pension (AOW) is paid out of workers’ contributions, as in the Spanish system.

The difference is that it constitutes a basic pension with a value related to the minimum wage. In addition, there is also a minimum welfare pension (AIO), which is a non-contributory pension for those who have not paid in for enough years.

The second component of the Dutch pension system is the occupational pension system, which consists of company pension plans for the workers and is used by the majority of employees. Ultimately, it is this that will account for the bulk of the pension they will receive, unless they also contribute to the third component.

That third component is the individual savings effort of each worker.

Pensions in Austria

In Austria they use the so-called Austrian backpack , which is nothing more than an individual capitalization system. Each month, companies contribute a part of the worker’s gross salary to a personal savings account that is managed by private funds.

This ‘backpack’ will go with the worker throughout their life, even if they change jobs. When they retire they recover the money and if, by chance, the investments have not gone well, the State ensures that they will recover at least the money they have contributed.

With this system, the amount of your pension will always depend on how much you have contributed.

The worker’s own private savings are, logically, added to this state savings fund.

Pensions in the United States

Contrary to what many think, the United States does have a pension system which is divided into three components: the state system, voluntary savings plans, and business plans.

On the one hand, there is a Social Security or mandatory social insurance. It works under a pay-as-you-go system and workers and companies both contribute to it. The workers accumulate credits according to the time they have worked and their salary; the pension then depends on these figures, although the amount of this pension is minimal.

As a result, most workers have no choice but to pay into to their own voluntary investment plans such as 401(k) plans, which are company schemes. Their distinctive feature is that most companies collaborate in these and double the investment made by the worker.

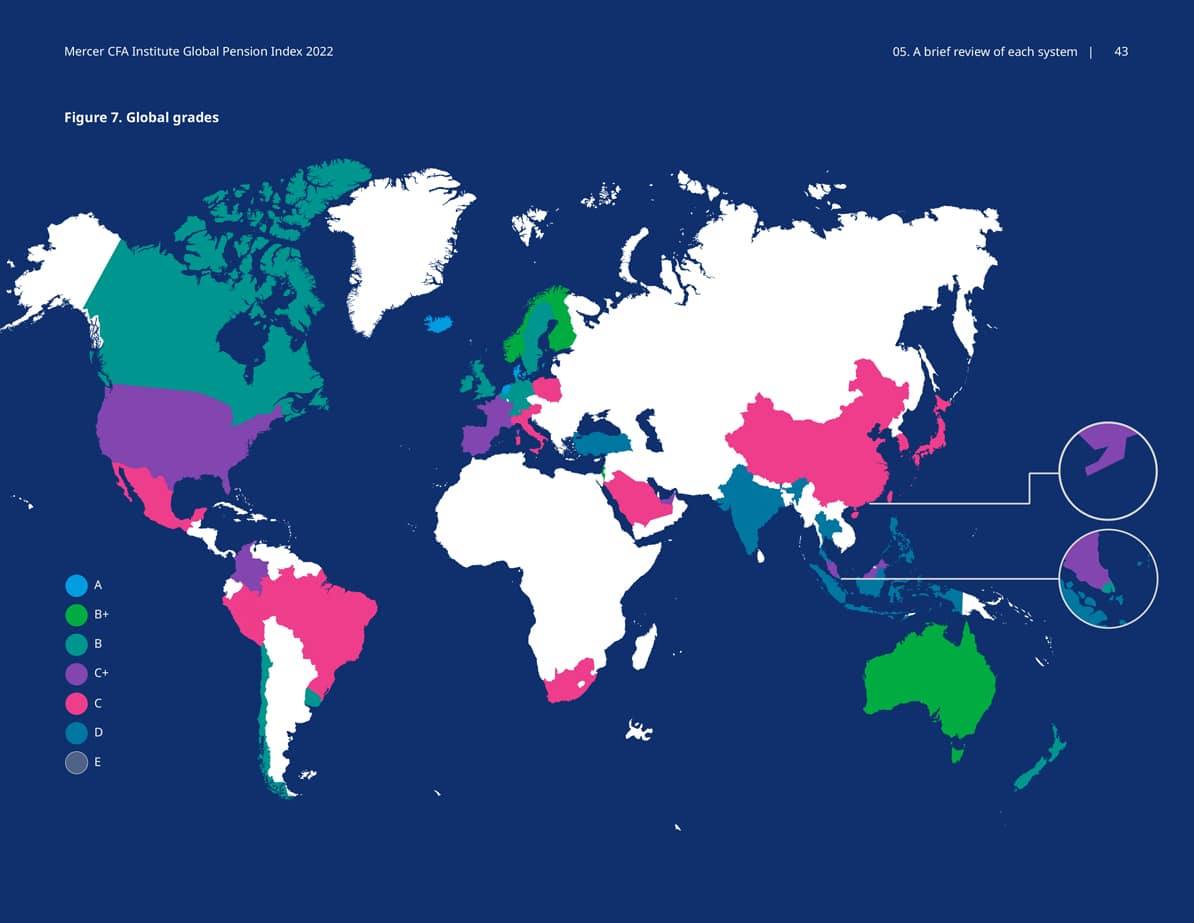

The best pension systems

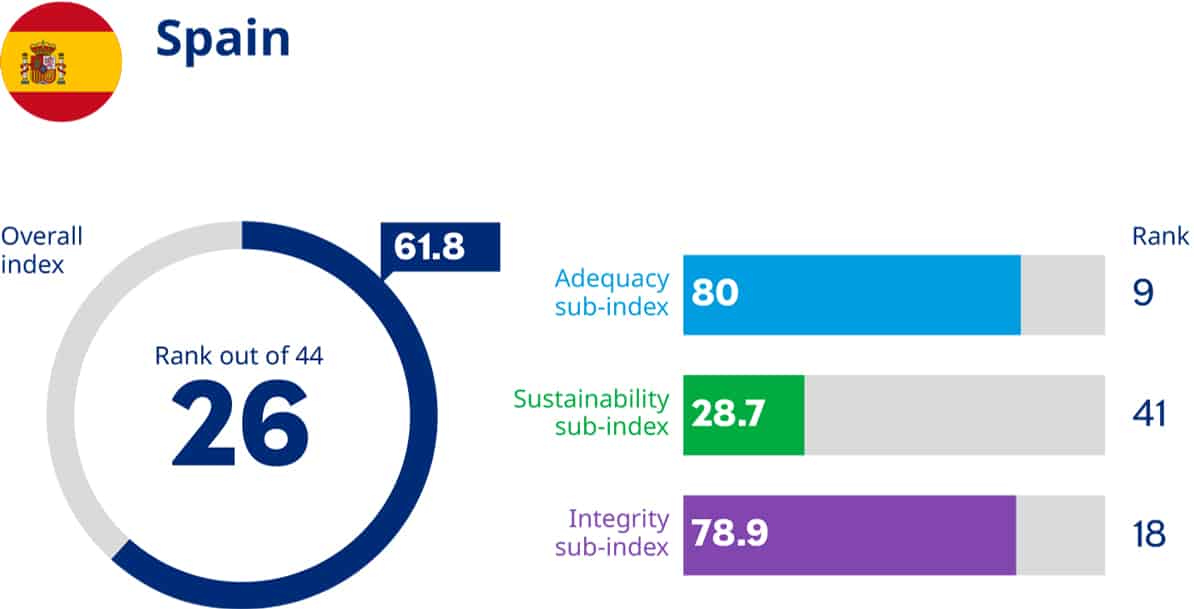

Different models and systems, but which ones work best? The answer is complex and, to answer it, the consulting firm Mercer and the CFA Institute publish the annual Global Pension Index report where they analyze the question from three perspectives:

- Adequacy of the system in terms of the level of basic income it provides and the design of the system itself.

- Sustainability of the system, which takes into account factors such as retirement age and the level of the country’s public debt.

- Integrity, which is marked by the laws and regulations that protect the system.

Under these parameters, the best pension systems in the world today would be:

- Iceland.

- The Netherlands

- Denmark.

And the best in each section:

Adequacy: Iceland, Portugal and the Netherlands

Sustainability: Iceland, Denmark, Netherlands.

Integrity Finland, Norway and the Netherlands.

And Spain? Spain occupies the 26th position with a score of 61.8, far from the top spot.